Randall Cox

I delivered newspapers in the nineties, setting out from my apartment in Mount Pleasant to a route in Jacksonboro. An eighty mile round trip, the route was an absolute disaster of a business plan. Worse than robbing Peter to pay Paul, it was more like robbing Peter and Paul to pay my own ransom.

I delivered newspapers in the nineties, setting out from my apartment in Mount Pleasant to a route in Jacksonboro. An eighty mile round trip, the route was an absolute disaster of a business plan. Worse than robbing Peter to pay Paul, it was more like robbing Peter and Paul to pay my own ransom.

“Downhill business,” as my mother used to say.

The paperboy’s friend, in the analog age at least, was the radio, and I toggled back and forth between AM and FM to stay awake as I rolled papers before dawn. On the FM dial, I stuck with the local alternative-rock station. I played in a band that was aiming for a Yo La Tengo meets Pavement vibe, and most of what they played on 96 Wave in the middle of the night suited me: “Today,” by the Smashing Pumpkins, for example, or “Feel the Pain,” by Dinosaur Jr. There was one song in heavy rotation, however, which irked me, a song I first remember hearing while delivering papers on a bleak, frosty Christmas morning. It was “Passenger Side” by Wilco, a woozy, country-tinged wobbler of a song which featured perhaps the single-dumbest couplet I’d ever heard:

“You’re gonna make me spill my beer/ if you don’t learn how to steer.”

In 1997, this was anathema to me. My (equally dumb) songs name-dropped Gertrude Stein, plagiarized Henry Miller. I was having nothing of “Passenger Side,” and for the next ten years, tuned out the entreaties of friends and bandmates to give Wilco a mulligan. No, I’d heard enough; “Passenger Side” was a serious misstep.

Ten years later, after a friend played Sky Blue Sky on a pontoon boat during a three-hour tour of Lake Jocassee, I began to realize that my anti-Wilco position was becoming increasingly untenable. The songs were beautiful, the playing and arrangements inventive, and the lyricist, it seemed to me, had climbed a few rhetorical plateaus in the intervening years. What’s the saying, none more fervent than the newly converted? Well, I’ve been a devotee of Jeff Tweedy and Wilco ever since.

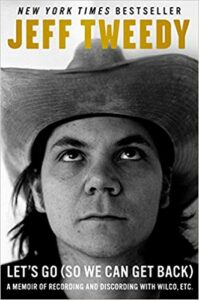

Jeff Tweedy’s debut as an author, Let’s Go (So We Can Get Back): A Memoir of Recording and Discording with Wilco, Etc.is a must-read for any fan, naturally, but also likely of interest to anyone who writes music or has interest in addiction issues. People with family dysfunction would probably go for this also. So yes, its content casts a pretty wide net.

Jeff Tweedy learned how to play guitar at the age of thirteen, in the aftermath of a bike stunt gone horribly awry. He wiped out in a drain water ditch and a shaft of rebar punctured his leg. “Puncture” is a bit of a euphemism, as the accident freed him from a substantial chunk of thigh-flesh, and necessitated in excess of one-hundred stitches.

Then, a nasty infection ensues, and the young Tweedy is confined to the bed, where he makes do by figuring out how to get good sounds to emit from the guitar (he’d attempted to play before, but was too impatient to stick with it).

The memoir contains a pair of crucially important Jays (Farrar and Bennet), and the author makes good on his promise early on to help his reader keep them straight. Tweedy is a high school sophomore with negligible social skills, a new-found love of punk rock, and a seriously fucked-up leg when he meets Jay Farrar. The two taciturn teens talk in monosyllables, but communicate through the records—and later, riffs—they exchange in the Tweedy family home in Belleville, Illinois, an exemplar of midwestern vacancy which boasts the nation’s longest uninterrupted Main Street and the most taverns per capita in the state.

Of his ultra-awkward, after-class introduction to Farrar, Tweedy writes, “I’m sure anybody watching was probably thinking, ‘Those two are going to start a band that plays a punk-country hybrid that a smattering of critics… will blow way out of proportion.’”

As someone familiar with the machinations of band-making, my interest here is grounded in Jeff versus the Jays, and how both musicians serve as necessary foils at defining moments in Tweedy’s development as an artist. Initially, he toils in the shadow of his new, more experienced friend, tentatively finding his voice and scratching out modest, inward-looking tunes while Farrar sings and plays with authority. Tweedy writes, “Jay was pretty much fully formed right out of the gate. He had a gift for lyricism, and an authentically great voice that made everything he sang sound like the Old Testament.”

The band they start together, Uncle Tupelo, records four albums and tours extensively, but just as the group is gaining real momentum, the inscrutable frontman Farrar quits. Tweedy feels abandoned, betrayed, and unprepared for whatever might be next. He’d become comfortable in his bandmate’s shadow, perceiving his own songs as little more than a complement to Farrar, while Farrar comes to believe that Tweedy is (passive-aggressively) angling to seize control. The demise of Uncle Tupelo will be familiar to anyone who has spent any time in a band: myth-making, imbroglio and turf-staking, substance-fueled insecurities and divided loyalties. One guitarist thinks the other is after his girl.

The Uncle Tupelo years engender an artistic confidence in Tweedy, but as he continues to write new songs and looks to form another band, his musical identity remains tethered to the notion of operating as Farrar’s foil. The first Wilco album, A.M., which includes the insufferable “Passenger Side,” is a testament to this mindset, but Tweedy is not ignorant of the dynamic and realizes that to grow as an artist, he’ll need to develop a musical identity distinct from Farrar and Uncle Tupelo. He writes, “I was still in the mode of writing songs as if they were one side of a conversation.”

Tweedy’s vision for his new band Wilco is brought to fruition by the formidable talents of the second Jay—Jay Bennett, a virtuosic guitarist who had opened for Uncle Tupelo during their run. Jay Bennett’s influence on Wilco’s eventual aesthetic, however, is born out of his uncertainty at a keyboard rather than his authority with a guitar. Tweedy hears Bennett plucking out the chords to one of their songs on the piano (the aforementioned “Passenger Side,” as it was), and the halting, uncertain approach clicks with the singer. “I don’t like too much confidence from a musician… I felt it more when he was struggling a little bit.”

This uncertain footing created a sort of floating foundation atop which Wilco would construct much of their ensuing material. Off-kilter synthesizers, found noise, and a plethora of ambiguous atmospherics have been Wilco mainstays for years. Tweedy gravitates towards Bennett’s mathematical, problem-solving approach to songwriting, and the two grow close, but after a couple of critically-acclaimed albums and sold-out tours, the band sours on Bennett’s penchant to seize credit for collaborative ideas; he is also hiding an escalating problem with pills. Tweedy is grappling with addiction himself, and begins to avoid his beloved studio just to steer clear of Bennett and his pharmaceutical supply.

In an act of self-preservation, Tweedy fires Bennett from the band, but offers to help him seek treatment for addiction. Bennet, unsurprisingly, denies the problem despite bountiful evidence to the contrary, and dies of an overdose eight years later, in 2009. Tweedy, meanwhile, befriends a rogue pharmacist/fan, and spends the next few years managing to function creatively while simultaneously abusing pills and googling variants of the phrase “Am I going to die?”

Catharsis comes, for Tweedy, when he comes to terms with an idea Bennett never could: “The drugs couldn’t keep up. Because of course they couldn’t.”

Coincidentally, the first record issued in the aftermath of Jeff Tweedy’s sobriety, Sky Blue Sky, was also the first Wilco record that I invested any time in. Plainspoken and patient in tone, less demiurgic than what preceded and what would follow, Sky Blue Skyrepresents a reboot of sorts, establishes a way forward. Not a “Passenger Side” to be found, and I’ve been on board ever since.

The genius of Let’s Goresides chiefly in its Tweedy’s vulnerability. The memoir provides an unflinching portrayal of one of the most unique voices in the last quarter-century of American rock and roll.

Randall Cox is an 8th grade English teacher from Locust Hill, South Carolina. Pedagogy being his sole professional concern (and a wanting one at that), he devotes what time he can to writing and recording music in the indie rock genre, hiking with his wife Kristie, and assembling with their children and grandchildren alike. He holds a BA in English from the University of South Carolina Upstate, and an MFA in Creative Writing from Converse College.

Randall Cox is an 8th grade English teacher from Locust Hill, South Carolina. Pedagogy being his sole professional concern (and a wanting one at that), he devotes what time he can to writing and recording music in the indie rock genre, hiking with his wife Kristie, and assembling with their children and grandchildren alike. He holds a BA in English from the University of South Carolina Upstate, and an MFA in Creative Writing from Converse College.