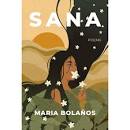

Sana by Maria Bolaños

Sana by Maria Bolaños

Published by Sampaguita Press on April 10, 2022

ISBN: 9798985771206

$20

60 pages

POETRY AS PRAYER IN THE DIASPORA

Review by Elsa Valmidiano

A review and analysis of Maria Bolaños’ debut poetry chapbook, Sana, arrives on the heels of the recent Philippine elections where a former dictator’s son has won the presidential seat. One may ask how this recent news from the Motherland has anything to do with reading Bolaños’ poetry. As seen throughout social media and major media outlets, the issue of apathy among Filipinos in the Diaspora, primarily from the United States, has emerged as a hot button response to the Philippine election, where the question is, Have our daily lives in the Diaspora taken up so much mental space that we have become apathetic where we no longer care to know what is happening in the land of our ancestors and for many of our families—immediate and extended—who remain there? In timely fashion, though Sana was written well before the results of the Philippine election became any cause for concern, a current reading of Bolaños’ Sana seems to tackle this very issue of apathy and disconnection as Bolaños herself is a diasporic child of the Philippines.

As seen in section I of her collection, Bolaños starts with a creation story, not just the Tagalog creation story of Maganda and Malakas that so many Filipinos are familiar with, but she touches upon her own creation. As reflected in the opening lines of her first poem, “Listening to Clouds”:

tell me the first name was the sound of beak against bamboo, the sound of a tree splitting when we emerged nameless sameness. One of us they called Crisostomo, and he became man. One of us they called Maria Clara, and I became ghost.

With beautiful imagery, Bolaños’ juxtaposes the Filipino creation story with her own birth, creating her own autobiomythography in the process of how she herself came to be. In reading the lines that follow:

Every memory starts with you had to be there, when I have no way to say this the way that I feel it.

I am reminded of a poignant statement by Mabi David, Filipina poet, who said, “You were not there. That is not your story. And consequently, I wondered, does it also mean that it is not my history?” As I consider Bolaños’ lines in conjunction with David’s quote, it is the desperate feeling of longing to know a history and land that feels so mysterious to us, not just due to the geographic separation of the Pacific Ocean, but that there is also the generational and survivalist divide where ancestral knowledge ordinarily passed on by elders feels lost.

Even as ancestral knowledge seems lost, Bolaños reimagines a lihim na karunungan (“secret knowledge”) through the simple and yet sacred everyday rituals practiced by the women in her family, captured in “Aubade”:

Memory and dream mingle and fade into the brightening sky. She, with her walis tingting, sweeping sleep from the concrete and clay of the doorstep, bent down to coax kisses upon the earth, wish-wishing good morning, good morning.

The intimacy of ritual resounds throughout the collection as followed up in “Prayer to My Ancestors” where despite the long-term effects of post-colonization that continues to replace, rename, and refashion our origin stories, Bolaños knows that ancestral prayer was never in the form of the colonizer’s words but that prayer was, and is, the body itself so that we are present-day spiritual vessels constantly in the process of healing old wounds carried and echoed generations later:

what is a body in pain but a prayer—what are our hands but our trauma: palms open, asking and asking

In section II of her chapbook, Bolaños additionally connects to her Motherland by revisiting Philippine folklore, where shapeshifters and apparitions are literary devices to honor, acknowledge, and make sense of the adopted homeland she currently resides in.

As seen in “Ballad of the Trickster,” Bolaños uses the trickster, also seen in many indigenous cultures, to examine the constant migration of diasporic bodies on land we now inhabit:

They call us stranger, outlaw, enemy. They don’t know our real names. They can’t understand me when I say to them: I am a mountain; I am a wind so wild it flows like freedom; I was born in a volcano; I come from a hundred lands. When I say these words, only the ones who have lost something, too, can understand. We nod to one another, they don’t see. They think it is only a myth.

Through the trickster who shapeshifts into a mountain, wind, or volcano, Bolaños’ lines call to mind the current plight of undocumented immigrants who are criminalized in this country and yet we know still belong to this land. She also seems to simultaneously address the plight of indigenous citizens whom white settlers othered and tried to ultimately erase as if they no longer are part of this land, while the white settlers themselves have gone on to steal and build this country on their own exclusive terms.

While apathy toward the Motherland among diasporic Filipinos might be more associated with privilege where issues at Home feel far removed and thus irrelevant, Bolaños herself has never been apathetic to the political situation unraveling in her Motherland. However as expressed in her poems, grappling with daily stress, the pandemic, and anxieties in one’s own life can be cause not necessarily for apathy, but more so the giving of attention to more pressing concerns, where the consideration for events back Home might become an afterthought as seen in “In the Last Days of the Kingdom”:

Each minute is a question: Am I ready to head this house? Am I ready to support all the families back home? Am I ready to die?

The immediacy of dealing with migration, survival, struggle, acclimation, and assimilation can leave little room for those in the Diaspora to ponder, leaving even lesser room to teach children the value and importance of keeping connected to the Motherland except in the rare moments where we might truly give ourselves pause to reflect on what and who we’ve left behind. The theme of responding to immediacy is followed up in “If You Want to Know Where I’m Really From, I’ll Tell You”:

I inherited my kulit from these men who scatter like ashes like stars across darkness, zigzagging their shine through Manila traffic out to California, to New York, to Saudi; out where young men go and become old men. I count down turns in roads with the names of soldiers & saints & American states & I’m gazing out at myself, visible only once every few years, wingtip blink of memory or ball of fire shedding my selves again, again. (41)

As the title of Bolaños’ collection, Sana, indicates an expression of hope and wishing, i.e. “if only,” her poems shape a complex love song to her Motherland as well as to her own diasporic body no matter where that body ultimately resides. It is in this love song that Bolaños breaks open her collection where we see how the very conditions in which we live can either lead us to apathy or longing in the Diaspora, and where despite what the revolving politics are in her Motherland, Bolaños’ poems pay homage to what is constant—the sacredness of family, and the power of cultural nuance and everyday ritual—which not only reminds us of Home, but also reminds us of our own resistance to oppression, our connection to the Motherland, and our lihim na karunungan—secret ancestral knowledge—allowing us to choose what gets carried forward wherever we are in our present and future.

—

Elsa Valmidiano is an Ilocana-American essayist and poet, and the author of We Are No Longer Babaylan, her award-winning debut essay collection from New Rivers Press. Her work is widely published in journals and recently appears in Cherry Tree, Canthius, Hairstreak Butterfly Review, MUTHA, and Mythos. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Mills College.

Elsa Valmidiano is an Ilocana-American essayist and poet, and the author of We Are No Longer Babaylan, her award-winning debut essay collection from New Rivers Press. Her work is widely published in journals and recently appears in Cherry Tree, Canthius, Hairstreak Butterfly Review, MUTHA, and Mythos. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Mills College.