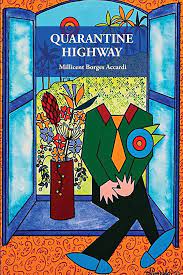

Quarantine Highway

Quarantine Highway

Poetry by Millicent Borges Accardi

FlowerSong Press, Sep. 2022

93 pp., $16.00

ISBN: 978-1-953447-35-7 (paper)

Review by Robert Manaster

Ideological, sentimental, or unfocused urgency are just some of the challenges to overcome when creating poetry about a collective tragedy, especially when writing in the midst of it. After three years into the Coronavirus pandemic, Millicent Borges Accardi’s fourth book, Quarantine Highway, is one such poetry collection that takes on these challenges. While her strongest poetry in this collection has effective tension in the poetic line, depth in language and tone, and a dynamic use of first-person plural perspective; the collection as a whole is not as strong as it can be if it had a more cohesive focus and a pace better integrating the pandemic with her Portuguese immigrant experience.

At her best, Accardi’s poetic line is varied and bare boned. The expanding and receding pace of enjambment contributes to the sublime, emotional strength of her poetry. When seemingly restrained via her poetic line, Accardi’s language seems as if it’s ready to burst out, as in “My Body is a Flame” (64):

Completely unfettered, I allow

what is to occur, unmethodical and edgy

to take over. I let it take over, fearing the other

shoe from falling out a window ten stories

above my head as I walk by,

These lines rupture and subvert cliché—waiting for the other shoe to drop—anticipating doom through this passage, which encapsulates Accardi’s confident voice. The winding-down lines, shifting caesuras, and varied (almost coarse) enjambment, enhance Accardi’s strengths—her voice and the tension her lines create.

In one of her stronger poems, ” Left with Loose Sentences” (28), about losing track of time during the pandemic, the incisive stripped-down poetic line seems to expose the speaker. The simile at the end of the poem—”as bottomless as a break / in the dark house up inside my heart”—shows Accardi’s considerable talent in the nuance of language. It has this strong unexpected, abstract ending rising in the word “up,” which opposes the momentum and force of “bottomless” and ever so slightly jolts the moment. “Up” can be hope, as in not bottomless, as in the heart is keeping itself “up” from bottomless despair; yet “up” also suggests being awake, as in “she stays up all night,” so it also implies a restlessness, an inability to sleep. In this subtle use of the word “up,” Accardi raises the stakes of this line and poem. Not only through this nuance but also through her phasing, Accardi is at her best here, as in “unmethodical and edgy” and throughout her collection, such as “a slick flush of wet jealousy” (from “And Admits,” 25) and “our converted nonchalance” (from “We Count Steps, Sweep Soreness,” 63).

Accardi uses first-person plural as a powerful rhetorical strategy, a tough poetic stance to take since the “we” can become dogmatic and preachy or implicitly dismissive of a reader who feels unattached to the speaker’s poetic sweep of inclusion. Accardi takes a risk and sometimes it backfires (not often). In the best poetry here, it’s either an authoritative and consistent “we” (whether the “we” of speaker and of partner, reader, Portuguese immigrant, Americans, or humanity) or it’s an unstable “we” that shifts within the poem where there’s depth in the various overlaying referents, as in the ending of “Yes, It’s Difficult” (23). “When she got the mumps at 40. It was simple and sweet / and maybe how life was meant to be when we held up our / wrists, someone came to pick us up and whisper hush.” Here, “we” seems to inhabit the personal (the female and perhaps others who have been sick) and universal (“we” as innocent children wanting help from our caregivers).

Most of the poems in this first half of Accardi’s collection involve the pandemic and its emotional impact. At times, it seems the same poem is written over and over (i.e., the pandemic is restrictive and bad, and before it, things were better though we didn’t know it). The poems in this half (and some in the other half) feel rushed out, and some of them could have been slightly edited more to bring out their strengths. It’s not surprising that an endnote reveals these poems were written during short time periods. Some of these poems could have been cut from the collection to make it stronger.

The last half of this collection (not separated as a section) contain poems more about Accardi’s past immigrant experiences. They tend to have a looser poetic line, which frequently enters into a more conversational (and narrative) tone. Their language seems more down-to-earth and has a physical sensibility. They operate more as a “breather-poem” versus the denser pandemic-infused poems, which tend more into abstract or ethereal moments. It’s as if the poetic style (not subject) in the last half opens up a space for Accardi and reader to take refuge in a safer more settled space—perhaps similar to a quarantine space.

As is, this long collection has more the feel of being two chapbooks or books. Accardi relies too much on the reader to infer what’s at stake outside the structure that this collection sets up, especially given an epigraph from the CDC about the origins of the word quarantine. It seems this quote is supposed to be connected with the 40 poems in this collection that are based on responding to someone’s line of poetry. This act of writing and sharing (and reading) during quarantine subverts the consequence of the pandemic—the isolation—and perhaps finds solace and beauty for Accardi and others poets connecting through the work. In this framework, Accardi’s collection could have thrived. Unfortunately. The limited frame of reference (of poets connecting) throws off the broader expectation of this collection’s structure and ignores how the immigrant experience fits in with quarantine or pandemic. In other words, there’s no doubt that these poems position themselves as being written while being quarantined. What’s a reader supposed to take away from that? This fact about constructing the book does not warrant that the collection cohesively works as a whole. What’s at stake?

Accardi’s move to connect her past, especially her immigrant experience, to the Pandemic is a worthwhile idea and move, but the execution of it is not as strong and integrated as it can be. Poems such as “With Beaded Rosaries Wrapped” (52) give strength to the collection’s foundation. Cutting down the collection and integrating this poem, and other ones on the immigrant experience, more throughout the first half would have made for a more powerful collection. As is, this bridge poem is about a funeral, yet “there was corona and distance and / no one can be there or get through / the walls that have been built.” This powerful image ultimately leads to this poem’s effective ending: “The rosaries / are named by her grandchildren and they slip / through our water like fingers.” The final simile turns cliché inside out, just like everything else in the pandemic. It disturbs this distant wall of keeping family and friends away while holding everything in. Such powerful poetry here invites a worthwhile conversation between quarantine and immigrant experiences.

Robert Manaster has published poetry book reviews in such publications as Colorado Review, Rain Taxi, The Los Angeles Review, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, and Massachusetts Review. His poetry has appeared in numerous journals including Rosebud, Birmingham Poetry Review, Image, Maine Review, and Spillway.

Robert Manaster has published poetry book reviews in such publications as Colorado Review, Rain Taxi, The Los Angeles Review, Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review, and Massachusetts Review. His poetry has appeared in numerous journals including Rosebud, Birmingham Poetry Review, Image, Maine Review, and Spillway.