Reprinted with permission from www.workinprogressinprogress.com

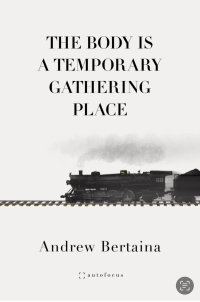

Give us your elevator pitch: what’s your book about in 2-3 sentences?

It’s a bit of a roundabout memoir in essays. The essays take place over about eight years of my life when I went through a lot of upheaval. Elevator pitch, it’s a mid-life crisis novel about parenting, divorce, identity and faith or lack thereof.

Which essay did you most enjoy writing? Why? And which essay gave you the most trouble, and why?

I had the most fun writing my essay “On Trains.” [See below for link.] I think it was the first essay where I hit on the idea of just riffing on a subject matter. Thus, it’s about wedding trains, how Einstein used trains to prove his special theory of relativity, a guide to trying to make love on a train etc, all mixed with intersections with trains from my own life. It felt very freeing. At the same time, it was a kind of challenge to scour my memories for train related content.

As for the hardest, I’d probably say the essay “On Baths.” I was closing in on the nadir of my mid-life crisis, deeply floundering, and I think that essay deals directly with the beginning of that fallout. I honestly don’t like to say any essay is too hard to write. It feels disingenuous when I’ve written the damn thing. Technically then, I’d say the essay “A Field of White,” because I had to find an internal structure to make it work. Otherwise, it was just too scattered. I like digressions; they mirror thought. However, internal structure is still useful, and I borrowed my structural device from John McPhee’s essay, “The Search for Marvin Gardens.” In my essay, the mooring point is a tea party I’m having with my three-year-old and her stuffed bear.

Tell us a bit about the highs and lows of your book’s road to publication.

Risking honesty, I wound up as notable in Best American Essays three out of the last four years. I know notable isn’t in the book, but I thought it might mean people would be clamoring for a collection. As always, my inbox was empty, so I had to figure out how I wanted to proceed.

My editor at Autofocus, Michael Wheaton, is an absolute gem, and he worked with me on finding a cohesive collection of essays. He was generous with his time and editing, and I’m deeply thankful to have worked with him. It ended up all right, but, as always in writing, I discovered the appetite for reading just isn’t that wide. But I have a beautiful book and a great set of essays that I’m proud of. They hold up.

What’s your favorite piece of writing advice?

I don’t own a single craft book volitionally. However, I think consistent writing is useful. Once you have a basic set of skills, it’s getting your butt in the chair. I often don’t, but I tend to feel better when I do. I tell my students who are struggling with it to just set a timer and do thirty minutes a day. That’s it. You can up it to four hours or whatever, but you should start small and build up. My paraphrase is, editing is writing, but you can’t edit nothing.

My favorite writing advice is “write until something surprises you.” What surprised you in the writing of this book?

I think I was surprised, mostly on a reread, with how much I was mentally suffering during the writing of these essays. In a way, it’s almost painful to go back and see so much wild energy and confusion without much purpose. I think it certainly captures something, and it’s not as though I have things figured it out now, but I was surprised at the kind of desperation I was giving off during those years, this mad desire to figure out life.

How did you find the title of your book?

The title of my book came to me in a dream. Okay. That’s a lie. But I like that lie. The title just seemed right. I meditate a bit. I don’t think the self is particularly real, and I think it’s even less solid for some of us, myself included. I have a hard time projecting myself into the future or feeling connected to my past. I have an essay that talks about it. Also, I think about death a bit. That life is temporary can be terrifying or beautiful. Choose wisely.

Inquiring foodies and hungry book clubs want to know: Any food/s associated with your book? (Any recipes I might share?)

I have an essay called “Eating Animals” in the book, but it includes several things that no reader would actually want to cook, including one’s spouse.

*****

READ MORE ABOUT THIS AUTHOR: https://andrewbertaina.com/

ORDER THIS BOOK FOR YOUR OWN TBR STACK: https://www.autofocuslit.com/store/p/the-body-is-a?fbclid=IwAR0xmIb08R6M7sXuZAAeNVv8P9rOpO5nR4sLpVtUpSZcyUy3v2QyF_KiZQ0_aem_Afb-FrxmnqNxojEQPW9ZOlCiA2xorxK8ktsNmdS3FV4yg7FMRBCbueRuRTeTxq-6oCTAJHaNvutOLKDJk0TjjZYr

LINK TO AN ESSAY FROM THIS BOOK, “On Trains”: https://greenmountainsreview.com/on-trains/

John Nizalowski is the author of four books: the multi-genre work Hooking the Sun; two poetry collections, The Last Matinée and East of Kayenta; and Land of Cinnamon Sun, a volume of essays. Nizalowski has also published widely in literary journals, most notably Under the Sun, Weber Studies, Puerto del Sol, Slab, Measure, Digital Americana, and Blue Mesa Review. Currently, he teaches creative writing, composition, and mythology at Colorado Mesa University.

John Nizalowski is the author of four books: the multi-genre work Hooking the Sun; two poetry collections, The Last Matinée and East of Kayenta; and Land of Cinnamon Sun, a volume of essays. Nizalowski has also published widely in literary journals, most notably Under the Sun, Weber Studies, Puerto del Sol, Slab, Measure, Digital Americana, and Blue Mesa Review. Currently, he teaches creative writing, composition, and mythology at Colorado Mesa University.